In the year 1746, everything seems to have been said on the subject of electricity and the interest of the "Philosophers of Nature" goes towards other curiosities. It was then that M. de Réaumur, a member of the Académie des Sciences, received a letter from his Dutch correspondent, Pierre Van Musschenbroek, which again boiled scientific Europe.

Electricity.

It began with his baptism by Gilbert, his popularization by Otto de Guericke and Hauksbee, his entry into the academic world with Gray and Dufay.

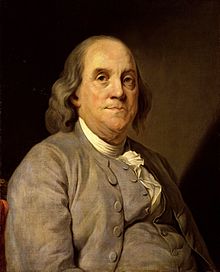

A man, in this new period, rises to the rank of the first of the "electrifying". He is a skillful experimenter: the abbot Nollet.

Terrible news from Leiden

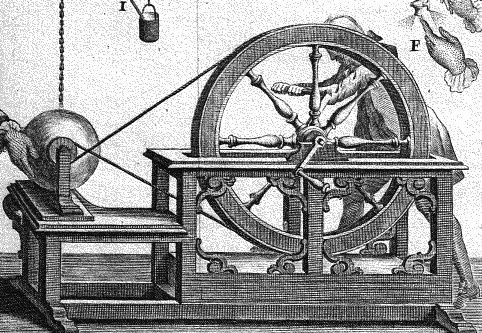

Pierre Van Musschenbroek (1692-1761) is professor of physics at Leiden and author of widely translated works. One day in 1746, one of his collaborators, M. Cunéus, was busy "electrifying" the water contained in a bottle. He holds it with one hand, a conductor connected to an electric machine is immersed in it. The method, as we will see, is unusual.

It is when he deems the bottle sufficiently charged that he has a painful surprise. He brings his free hand closer to the conductor immersed in the bottle. At the same moment his hand is struck by a noisy spark, his body writhes in a spasm of extraordinary violence. An unbearable pain overcomes him. Pierre Van Musschenbroek and his colleague Allamand, informed of the miracle, verify the phenomenon. It is Musschenbroeck who informs learned circles of all the capitals of Europe.

L’expérience de la Bouteille de Leyde (Les Merveilles de la science)

His letter will be read on April 20 in Paris during a session of the Academy of Sciences and commented on by Abbé Nollet:

"I want to communicate to you a new but terrible experiment which I advise you not to attempt yourself... I had suspended from two silken threads an iron cannon, AB, which received by communication the electricity of the glass globe, which was rapidly rotating on its axis, while it was rubbed by applying the hands to it; at the other end B hung freely a brass wire, the end of which was plunged into a round glass vase D, partly filled of water which I held in my right hand F, and with the other hand E, I tried to shoot sparks from the electrified cannon: suddenly my right hand F was struck with such violence that I had the body shaken as from a thunderbolt; the vessel, though of fine glass, does not usually break, and the hand is not injured by this shock, but the arm and the whole body are affected by a terrible way that I cannot express: in a word, I believed that it was the end of me”.

Another letter from Leyden confirms this testimony. It is from M. Allamand.

“You must have heard of a new experience that we have done here (the description of the experience follows)... You will feel a prodigious blow which will strike your whole arm, and even your whole body, it is a thunderbolt; the first time I tried it, I was so dazed that I lost my breath for a few moments: two days later, M. Musschenbroek having tried it with a hollow glass ball, he was so deeply affected that a few hours later, having come to my house, he was still moved by it, and told me that nothing in the world would be able to make him try the thing again."

The abbe Nollet, who knows the seriousness of his interlocutors, approaches this new experience with a certain apprehension. The result confirms his apprehension.

"I felt in my chest and in my bowels, a shock that made me involuntarily bend my body and open my mouth".

Terrible ! Such is the phenomenon. Gradually, however, it is domesticated and the primitive terror fades. Electricity then descends into the streets, or rather into the gardens and parks, where, as Abbé Nollet notes, it “shows itself to the people”.

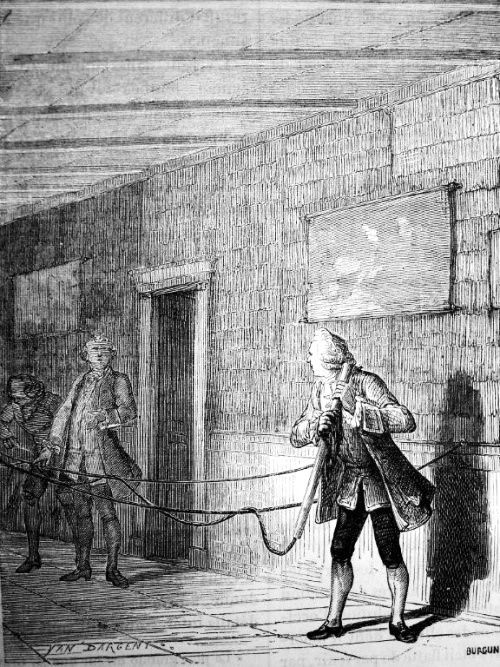

We were not without noticing that two people holding hands simultaneously receive the electric shock when, one carrying the bottle, the second touches the conductor connected to the machine. Two people, then three... the chain gets longer.

Nollet is not the last to engage in these “media” demonstrations. He imagines unloading a bottle of Leyden through the chain formed by three hundred soldiers of the French guards holding hands. The people should not have been indifferent to the spectacle of these “guardians of order” shaken by the electric shock. Better: monks forming a conductive chain around their abbey will prove, by jumping in the air all together under the effect of the electric discharge, that it propagates at an extraordinary speed. At least this is how rumor translated a wiser experiment carried out by Lemonnier in the Carthusian convent.

Everyone strives to offer a different scenario: a doctor uses the Tuileries basin to transmit electricity. A certain prince, at the end of an opera performance, applauds a demonstration of electric shock presented on stage by the actors.

We also exchange recipes. Abbot Nollet offers several:

"Try the Leiden experiment with a porcelain coffee cup, with a rock crystal bottle, if you can get one, or with one of those little brown pots in which butter from Brittany is sent to Paris and to that of Normandy; and that will succeed for you.

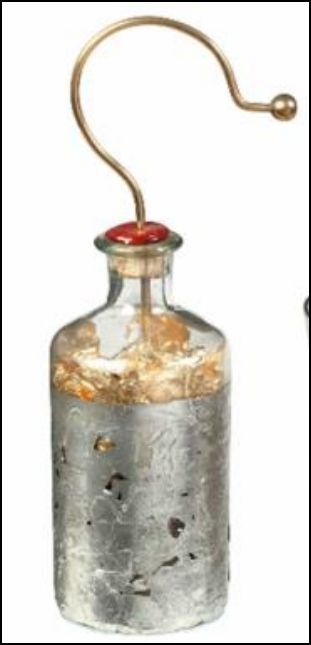

The Leyden bottle is therefore the first “electric capacitor”. It may seem surprising that such a spectacular observation was only made so late.

The fault perhaps lies with Dufay. Having been one of the first to electrify the liquid contained in a bottle, he had inaugurated a strict method, often referred to as "Dufay's rule". The electrical fluid must not be able to escape from the bottle. For this, the vase containing the liquid had to be made of thick glass and, above all, placed on a perfectly insulating support! An academic electrician would never have deviated from the rule. It therefore took a poorly informed experimenter to break with this tradition. This poor manipulator was however going to provoke, without having sought it, a revolution.

How does this bottle work?

Musschenbroek, the first, admits his ignorance: he no longer understands anything, he says, and can no longer explain anything about electrical phenomena. A bottle held in the hand should never have been able to be charged, especially if it was made of thin glass. The electrical fluid had to pass through the thin thickness of glass to flow without difficulty towards the earth through the body of the operator. Yet it was this ridiculous assembly, this manipulation outside of all the rules, which had caused the most violent phenomena ever observed.

Better ! The more the glass is thin, the more violent the shaking. The more contact with the ground is ensured, for example by covering the external part of the bottle with a sheet of metal, the greater the efficiency will be. Everything seems to work opposite to what is expected. Those who attempt an explanation quickly give up: the Leyden bottle remains an exception. We'll use it but we'll forgo finding out more for now. Once again, it will take an observer without academic training to overcome the obstacle. It will be Franklin once again.

It should be remembered that Franklin imagines a unique electrical fluid which permeates all bodies and which can simply be accumulated or rarefied by means of devices acting as "pumps". It is again this model which allows him to interpret the functioning of the Leyden bottle in a truly convincing manner. The wire connected to the machine and dipping into the liquid in the bottle pushes back, he says, an excess of electrical fluid into it. At the same time, the same quantity of this fluid is repelled through the glass and expelled, from the external metal frame then from the hand of the observer who carries it, towards the earth.

In reality, as Franklin said, the bottle is not really "charged" with electricity because, "whatever quantity of electric fire passes through the top, an equal quantity comes out through the bottom." The phenomenon stops when it is no longer possible to get more electricity into the bottle, that is to say when "it can no longer be extracted from the lower part". When this moment arrives, a strong positive charge has accumulated in the bottle while an equivalent lack has been created in the external armature.

From then on, the “electric shock” is clearly explained. By connecting the internal and external parts of the bottle by a conductive body, balance is suddenly restored. If this conductor is a small diameter metal wire, it can become incandescent or even melt. If it is a person, they will experience a shock that they will not soon forget. If it is a small animal, it could lose its life.

Franklin's interpretation aroused the enthusiasm of many supporters among those who had been left thirsty by the mystery of the Leyden bottle. This will also irritate many. Nollet, for example, cannot give up losing its place as “first” European electrician. A controversy arose between him and Franklin over the question in which part of the bottle the electricity accumulated.

Nollet believes that it is the water in the bottle which concentrates the electricity and he proves it: a bottle full of water being charged with electricity, pour this water into another bottle placed next to it on a pedestal table. You will find that this second bottle is quite capable of giving you an electric shock. The electricity was therefore transmitted with the water in the bottle.

Franklin asserts on the contrary that it is in the glass that this accumulation is located and he also proves it: a bottle full of water being charged with electricity, pour this water into another bottle placed next to it on a table, as Father Nollet recommends. You will notice that this second bottle is completely incapable of giving the slightest electric shock. On the other hand, the first bottle, although empty, retained all its potency. This can easily be seen by refilling it with uncharged water. The electric charge was therefore well preserved in the glass.

Two opposing observations for two absolutely identical experiments? One clarification, however: the pedestal table on which Abbé Nollet places his second bottle is made of a conductive metal, contrary to the rule published by Dufay. Franklin's is covered with a very dry plate of glass, which does not correspond to the standards of the Leiden experiment!

We leave it to the informed reader to decide between these two doctors. We will simply observe that Franklin, emphasizing that water plays no role in this matter, does not need a container to contain it. He will therefore use, instead of bottles, glass tiles placed between two lead blades of slightly smaller size. A layout close to that of our current capacitors. Nollet, for his part, popularized the traditional bottle, easy to bild and simple to use. However, he will replace the water with lead shot, iron filings or better, crumpled gold leaf. In this form, the Leyden bottles, often combined in batteries, will spread to the most unexpected places. For example in the doctor's office.

Very early on, the therapeutic effect of this miracle bottle was envisaged. One had barely had time to ascertain some of the properties of electricity when a whole world of healers lacking respectability or doctors waiting for clients had already seized it. Already yellow amber, then called succin, was a traditional element of the pharmacopoeia, it was therefore logical that we seek to use its essential "principle", the electric fluid, this vital fluid which already allowed Thales to “give life to inanimate beings”.

To Give life or take it: Bose killed flies by striking them with the spark flying from his outstretched finger. Nollet kills sparrows by using a Leyden bottle. Franklin kills a turkey by discharging an entire "battery" of loaded bottles through the poor animal.

Take life or give it back: a previously drowned sparrow is brought back to life by the discharge of a bottle. A hen is resurrected by the same means. The Leyden bottle really works miracles.

It is easy to imagine the benefits that could be gained by skillful manipulators from these machines capable of extracting "fires" and other "effluvia" from this or that diseased organ of their patient. Collecting the entire medical “bloopers” of the 18th century would require several volumes. Father Berthollon, a famous and often translated popularizer, sees electricity as a real panacea: it makes you lose weight, it even makes your hair grow back! It is possible to give vigor to indolent natures by administering positive electricity to them and naturally to calm the nervous with negative electricity. Electricity promotes flow: electrifying the patient during bleeding gives a jet of blood that is “lively, dilated and extending far away”. Mr. Jallabert, professor of "Experimental Philosophy" is categorical, no one can question the results obtained on his patients "and if some doctors have seen contrary examples, I suspect that fear or someone other particular obstacle , will influence the experience".

A fear certainly justified and which could only grow from the moment the Leyden bottle came to strengthen the healer's arsenal. Father Nollet was the first to try to apply electric shocks to a paralytic. Judicious approach when we notice the involuntary contractions thus caused. The beginnings seem encouraging: under the effect of the shock the patient sees muscles that have been inert for a long time contract. But autonomous motor skills do not return and we must give up. However, some cases of cure are announced, many paralytics voluntarily expose themselves to electric shock. One increase the capacity of the Leyden bottles, one combine them into batteries and, soon, one are very close to killing our patient because they are no longer pleasant sparks coming out of these devices.

Mr. Jallabert, for example, wants to reinforce the effect of the shock by using hot water. One day he uses boiling water:

"I substituted boiling water for hot water. Very bright flashes appeared of their own accord before you put your hand near the vase: they become even brighter and more numerous when you put your hand on them. at the moment when the person, who touched it with one hand, with the other drew a spark from the bar, the fire with which the vase was filled suddenly appeared with inexpressible vivacity. At the same moment an orbicular piece of the vase of 2 lines and half diameter was thrown against the wall which was five feet away...

The astonishing vivacity of a fire which cannot be better compared to that of lightning; this incredible phenomenon of a vase pierced by the action of electricity, the terrible shock felt by the one who pulled the spark: all this had impressed on the spectators a terror which did not allow me to expose any from them to a second torture.

...a fire that one cannot better compare to that of lightning...

Already, in his first letter the image had been used by Musschenbroek: "my whole body shook as if by a thunderbolt...". Is it just an image or is there really an identity between lightning and electric discharge? The idea has been in the air for several years. Father Nollet had already suggested it. It is surprising to note that the years go by without any European scientist really seeking to explore this analogy further. It will take an American "amateur", Franklin again, to shake up old Europe and revive interest in electrical science.

/image%2F0561035%2F20140324%2Fob_6b7b8e_003-vinci-dodecaedre-02.jpg)